Do you dream about your work? A colleague of my father’s once invoiced an employer to compensate his sleeping hours. (Purportedly, he had solved a problem in a dream.) Because chemical engineers are expected to sleep on their own time, his request was denied.

Billing for dreams may sound ludicrous and pretentious, but I get it. Invest enough time and energy into your work, and it will seep into your subconscious and haunt your dreams.

Teaching artists spend the majority of our waking hours helping others to connect to an artwork’s essence. When all goes well, people become transfixed or transformed by it. We dream about this, figuratively and literally.

On a good night, a teaching artist dream inspires a new, complete lesson plan: you have a vision of people standing in a circle and simulating a fugue as they bounce and pass basketballs. On a bad night, we relive the times that we miserably failed to bring others into the magic of a masterpiece. In the teaching artist nightmare, things get weird and nerdy pretty quickly. . .

A Teaching Artist Nightmare

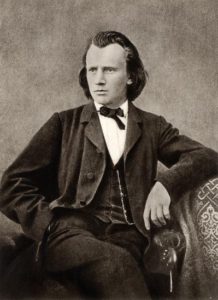

Last night’s teaching artist dream was abysmal. At a noisy, crowded dinner party, the stranger seated beside me randomly asked me why I love Johannes Brahms’s Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98. (Go ahead; judge my repressed desires. . .)

Taken off guard, I rambled incoherently. Oh, I was passionate all right. I listed musically solid reasons: intervallic relationships, compound meters, architectonic layers of rhythmic pulsation. . . Perceptually speaking, though, I gave my polite listener absolutely nothing of value. (Did I mention Phrygian melodies?)

I summarized the finale’s greatness with a simple sentence:

“The fourth movement. . .”

[emotionally charged pause; right index finger rises unconsciously for added emphasis]

“. . . is a passacaglia!”

With that utterance, I choked up and held back tears. -In dreams, who doesn’t weep at the thought of an inspired, German genius concluding a romantic symphony by resurrecting a seventeenth century Spanish dance form?

-The normal guy sitting next to me, that’s who. He repays all my vapid effusion with a blank stare.

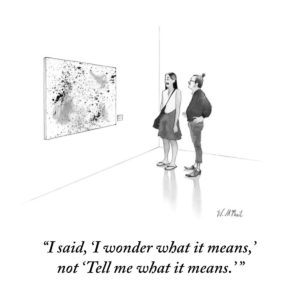

He’s right, of course. As an advocate, I’ve been an idiot. Abstracted from musical experience, my subjective emotions, formal analysis, historical knowledge, and classical music jargon provide no vehicle for listening, comprehending, or caring. The man neither hears what I’m hearing, nor knows what I’m knowing. He can’t tap my dopamine.

The Teaching Artist Nightmare Never Ends

So, the stranger tries to help by asking some well-meaning questions: “Yeah, but is it going anywhere? I mean, does it lead to something? Is there some kind of highlight?”

It’s my turn to stare blankly back.

So that’s it? For you, music goes somewhere? Symphonies revolve around a main event, some kind of climax that you can point to and say, “Whoah! How ‘bout that bass drum?!” The entirety of Brahms IV culminates in a marvelous passacaglia; did I not make that clear?!

“Well. . . kind of. Things really amp up at the golden section. But for me personally, the highlight is this flute solo. . . Um let me. . .”

I fumble around, looking for my score. (Doesn’t every teaching artist bring a reprint of the Vienna Gesellshaft der Musikfreunde’s complete Brahms symphonies to the dinner party?. . .)

I stop rummaging, realizing that I forgot to bring my music- a common occurrence in a teaching artist nightmare. Even if I had, notes on the page would have proven silent and impotent. My only recourse is to stand and sing the flute solo myself, finally channeling my passion into music rather than verbiage. I take a deep breath. . .

Mercifully, I awoke. I felt terrible.

Escaping the Teaching Artist Nightmare

I felt awful because I had violated just about every tenet of effective teaching artistry. Instead of listening, I was talking. Instead of questioning, I was telling. Rather than cultivating a listener-centered inquiry into the symphony, I fell into the trap of focusing on my own personal enjoyment and interpretation.

Unfortunately, I drowned perfectly valid entry points with unexplained terminology. I conveyed information without engaging through actual musical experiences. Honestly, the guy didn’t really want to know why I love Brahms IV. On the contrary, he wanted to love Brahms IV himself.

I’m reminded why I give pre-concert talks with a fiddle in my hands and a piano at my side. I’m recalling why I make my learners conduct Brahms’s phrases, sing his melodies for themselves, or perform his complex rhythms as a group.

When you are teaching others, consider which technical terms you critically need to communicate, and which are superfluous and omissible. Ask questions of an artwork, rather than assuming that you already have all of the answers. Instead of forcing people into a prescribed experience, set them up to discover the highlights for themselves.

Let’s wake up. The strangers are listening.

-Doc Wallace, 9 February 2017

Follow Doc!